When we have to understand challenging speech - for example, speech in background noise - we have to “work harder” when listening. A recurring challenge in this area of research is how exactly to quantify this additional cognitive effort. One way that has been used is self-report: simply asking people to rate on a scale how difficult a listening situation was.

Self-report measures can be challenging, because they rely on meta-linguistic decisions: that is, I am asking you, as a listener, to have some insight into how difficult something was for you. It could be that people vary in how they assign a difficulty to a number, and so even though two people’s brains might have been doing the same thing, the extra step of having to assign a number might produce different self-report numbers. Because of this and other challenges, other measures have also been used, including physiological measures like pupil dilation that do not rely on a listener’s decision making ability.

At the same time, subjective effort is an important measure that likely provides information above and beyond what is captured by physiological measures. For example, personality traits might affect how much challenge a person is subjectively experiencing during listening, and a person’s subjective experience (however closely it ties to physiological measures) is probably what will determine their behavior. So, it would be useful to have a measure of subjective listening difficulty that did not rely on a listener’s overt judgments about listening.

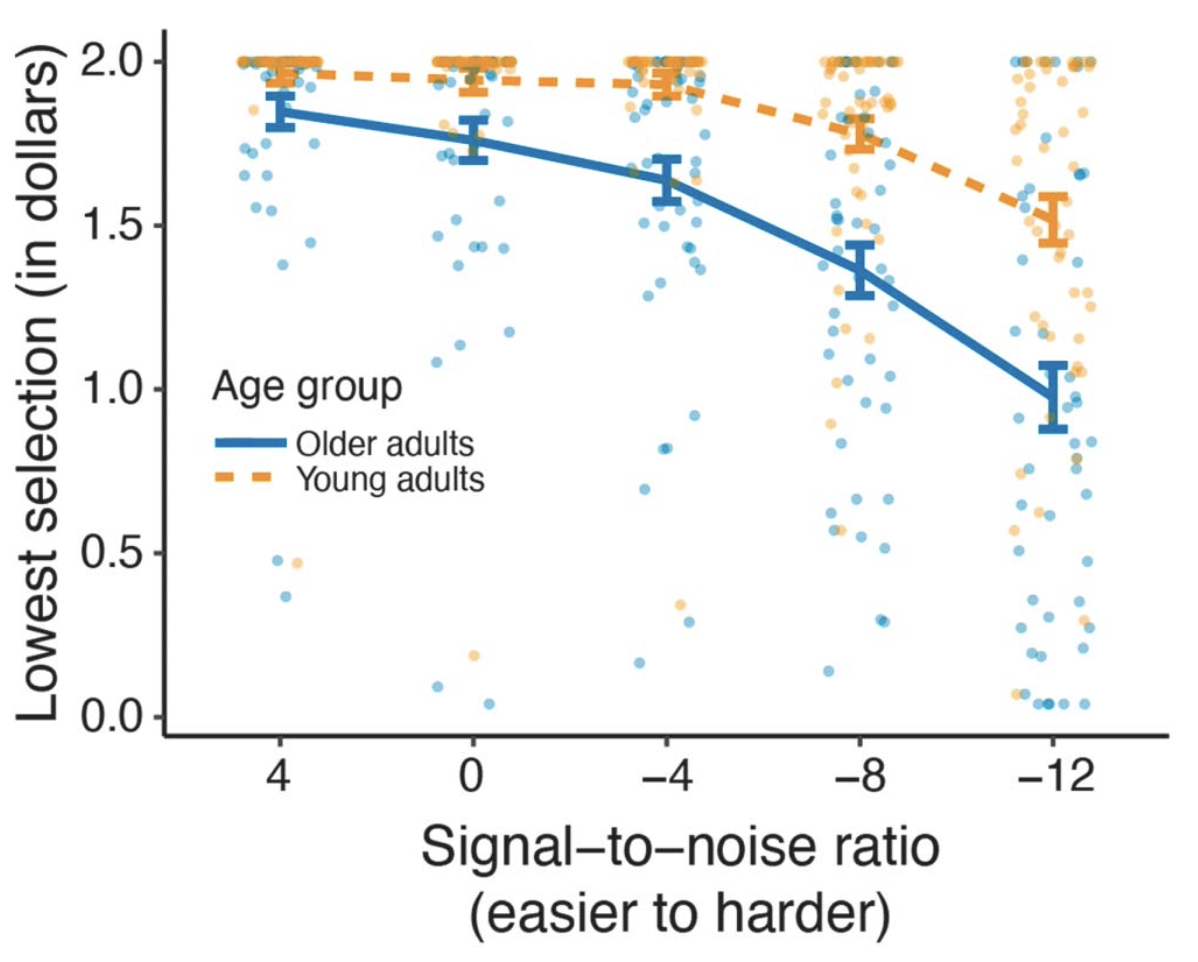

Drew McLaughlin developed exactly such a task, building on elegant work in non-speech domains (McLaughlin et al., 2021). The approach uses a discounting paradigm borrowed from behavioral economics. Listeners are presented with speech at different levels of noise (some easy, some moderate, some difficult). Once they understand how difficult the various conditions are, they are given a choice on every trial to perform an easier trial for less money, or a difficult trial for more money (for example: I’ll give you $1.50 to listen to this easy sentence or $2.00 to listen to this hard sentence). We can then use the difference in reward to quantify the additional “cost” of a difficult trial. If I am equally likely to do an easy trial for $1.75 or a hard trial for $2.00, then I am “discounting” the value of the hard trial by $0.25.

We found that all listeners showed discounting at more difficult listening levels, with older adults showing more discounting than young adults. This is consistent with what we know about age-related changes in hearing and cognitive abilities important for speech that would lead us to expect greater effort (and thus more discounting) in older adults.

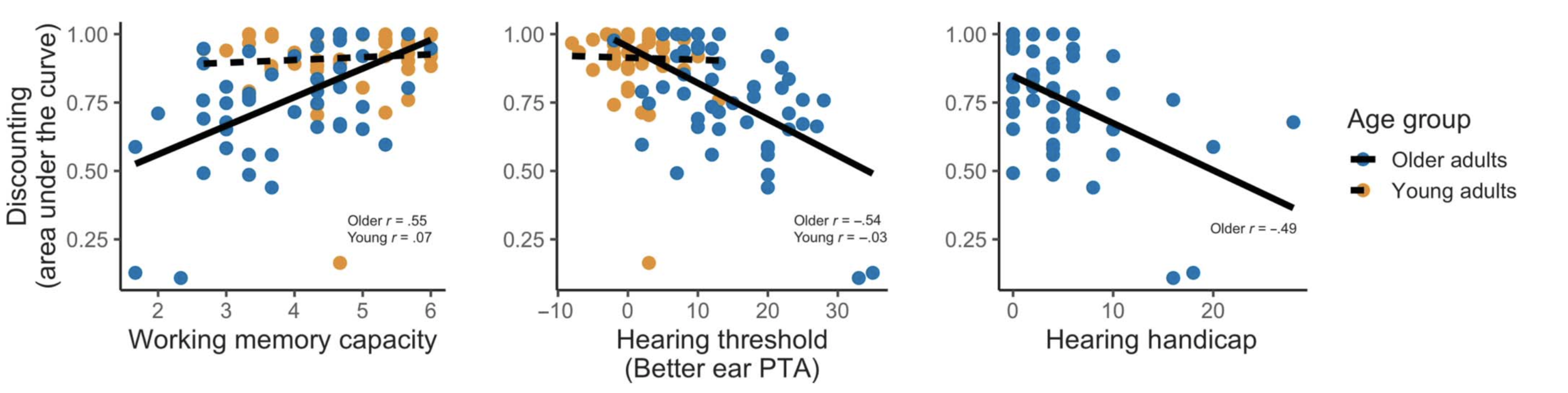

To complement these group analyses, we also performed some exploratory correlations with working memory and hearing scores. For the older adults, we found that listeners with better working memory showed less discounting (that is, found the noisy speech easier); listeners with poorer hearing showed more discounting (found the task harder). We also looked at a hearing handicap index, which is a questionnaire assessing subjective hearing and communication function, which also correlated with discounting.

I’m really excited about this approach because it provides us a way to quantify subjective effort without directly asking participants to rate their own effort. There is certainly no single bulletproof measure of cognitive effort during listening but we hope this will be a useful tool that provides some unique information.

Reference

McLaughlin DJ, Braver TS, Peelle JE (2021) Measuring the subjective cost of listening effort using a discounting task. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research 64:337–347. doi:10.1044/2020_JSLHR-20-00086 (PDF)