How does your brain respond when you lose the use of a limb? When a professor needed achilles surgery that required no weight-bearing in his right leg during recovery, it provided the perfect opportunity to find out. Introducing the Health, Exercise, And Longitudinal Indexing of Neuroplasticity and Gait (HEALING) study.

As of December 31 2025, we have 47 sessions of structural and functional MRI (including ~ 9 hours of resting state data), 35 sessions of high-density EEG , 27 sessions of fNIRS (including resting state and walking/locomoting), and somewhere in the neighborhood of 900 EMA observations.

Research team

The principal investigators are all faculty at the Northeastern Institute for Cognitive and Brain Health and include:

along with a tremendous amount of help from graduate students, research coordinators, and staff.

Inspiration

Several prior studies provided scientific inspiration for looking at brain plasticity and limb disuse, as well as setting examples of dense sampling in a small number of individuals (where “small number” might also just be one):

Russ Poldrack’s MyConnectome project where he had MRI scanning, blood work, and surveys over 18 months (100 total resting state fMRI sessions).

Work from Nico Dosenbach and colleagues looking at precision mapping of resting state networks in individuals, and especially how networks change with limb disuse (Nico and two grad students put their dominant arm in a cast for 2 weeks!)

Achilles troubles provide a natural experiment

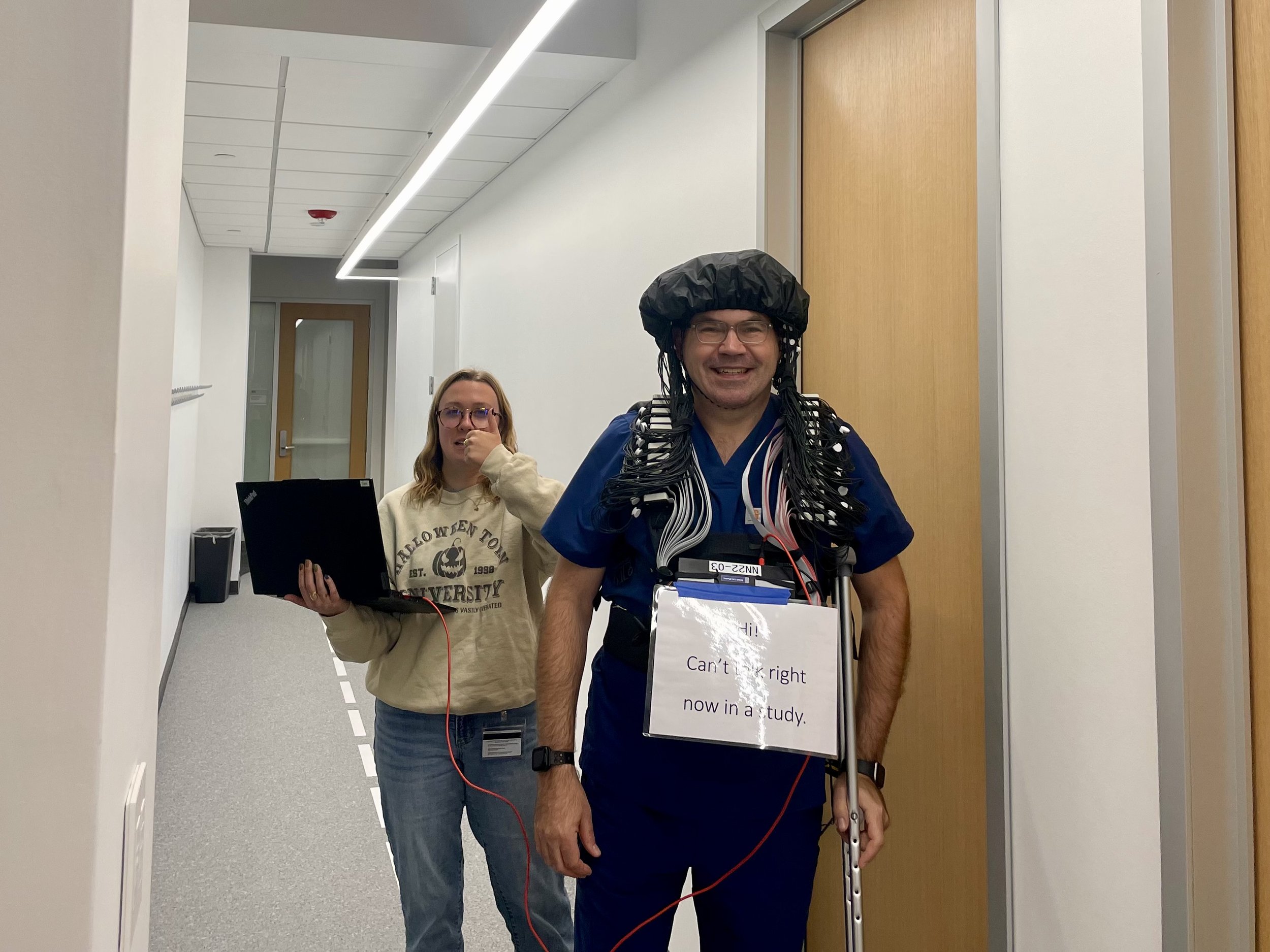

X-ray showing bone growth on the back of Jonathan’s heel

For well over a year, Professor Jonathan Peelle had a tender Achilles tendon. Physical therapy helped some, but couldn’t solve the problem, which was due to a bone growth on the back of his heal (a Haglund’s deformity). As long as the bone was rubbing the tendon, there would be pain. Jonathan’s surgeon recommended a repair which involved removing the tendon, getting rid of the bone, and then reattaching the tendon (video here). The recovery would require much reduced weight-bearing for a period of several weeks (using a scooter or crutches for at least 2 weeks). Remembering the above-mentioned study on limb disuse and brain plasticity, Jonathan thought this would be an excellent chance to see if limb disuse in a surgical context—which also includes general anesthesia, doctor’s appointments, and so on—would match what was found in controlled conditions. He talked to several colleagues who were also interested in various aspects of exercise, mental health, and brain plasticity, and HEALING was born.

Because the surgery was scheduled in advance, we were able to collect a month of baseline data for our primary measures, continuing data collection until a month after full weight-bearing resumed.

Data collection

The comprehensive data set includes:

Daily ecological momentary assessment (EMA) data on pain, affect, and other lifestyle factors;

Accelerometry data (wrist and both ankles)

Low-density EEG (resting state, visual evoked potentials), collected at home

Brain measures (2x/week)

Structural MRI (T1)

Functional MRI (7.5 min resting state x 2, 10 min of movie)

Magnetic resonance spectroscopy (to look at GABA in motor cortex)

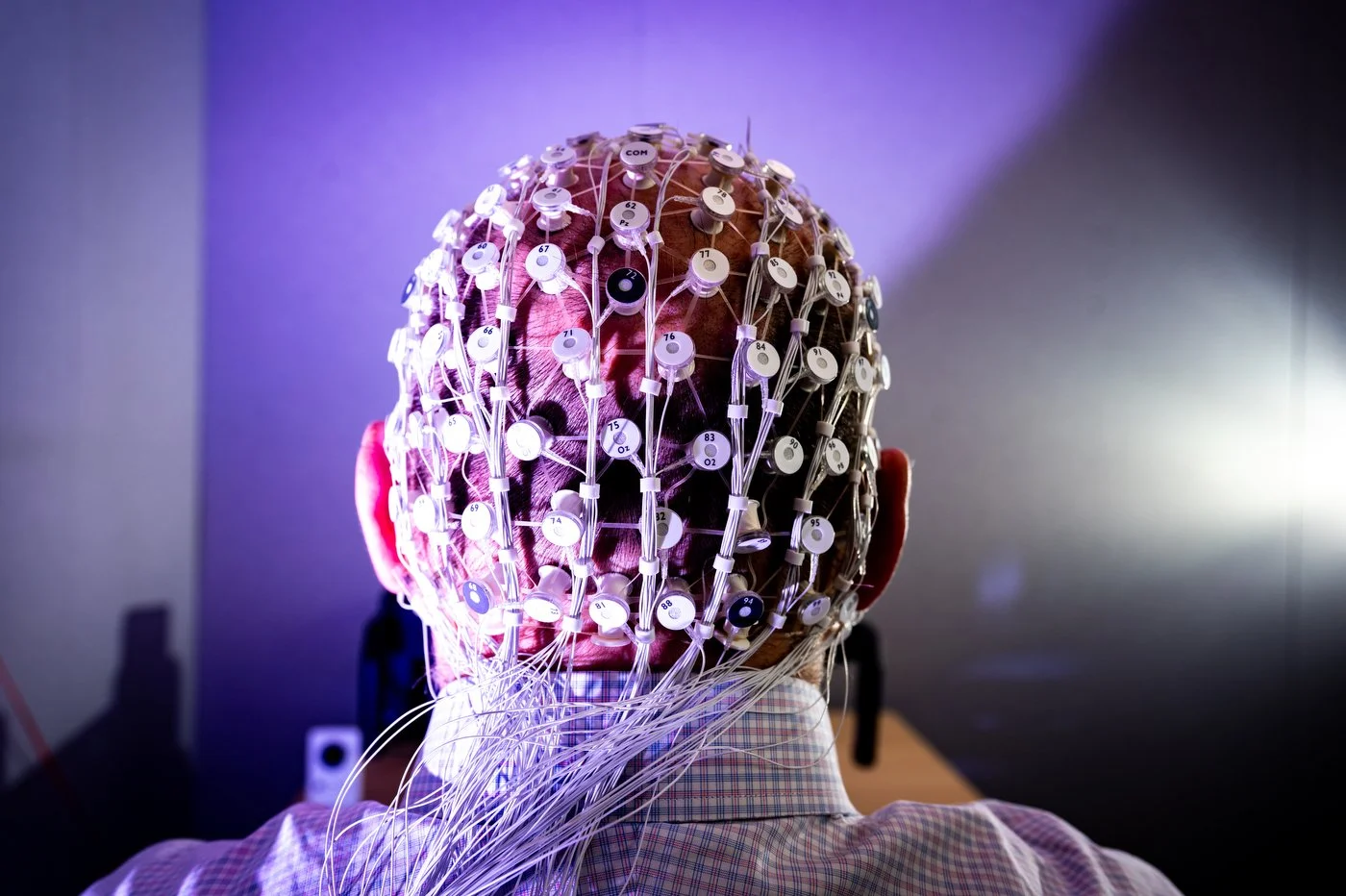

High-density EEG

High-density fNIRS (using a NinjaNIRS system with 144 detectors and 56 sources)

Brain measures (periodic)

PCASL

DTI

Iron

Salivary cortisol (periodic)

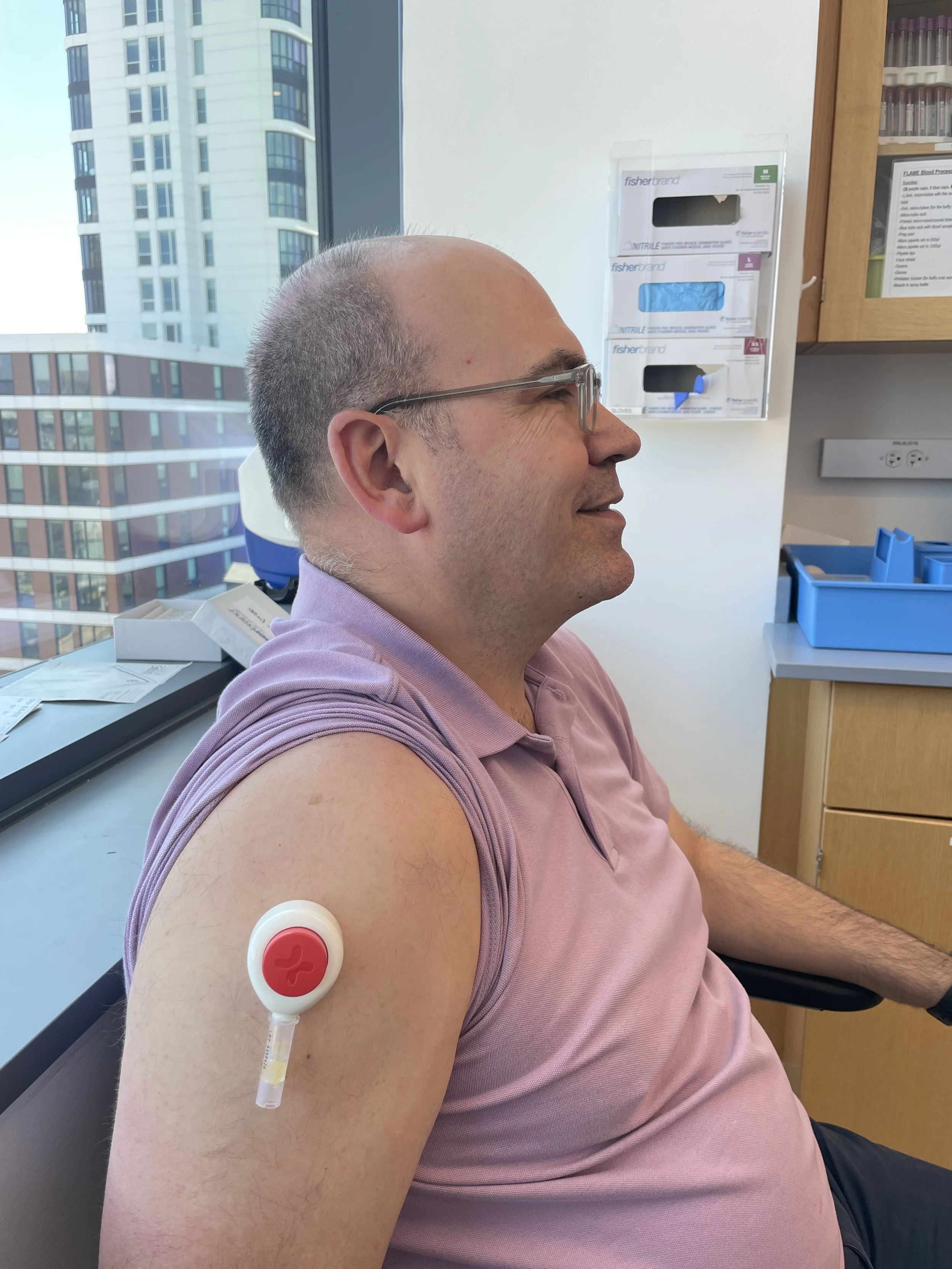

Blood (1-2x/week)

DXA (periodic)

VO2max (periodic)

Physiology and reflex (periodic)

Photos above by Alyssa Stone/Northeastern University

Schedule

Jonathan’s surgery was September 25, 2025. MRI, EMA, and HD-EEG data collection began August 25, 2025, although some minor alterations to protocols occurred over the first 1-2 weeks.

Data availability

When the time comes all data will be publicly shared.